| friends |

av archive |

bairnrhymes |

bookcases |

buses |

calendar |

grave |

lectures |

| makars |

music |

panels |

prize |

roll |

schools |

sculpture |

shows |

the arch |

theatre |

| walks |

Soutar Birthday Lecture

For the Luve o a Lied

The Soutar Festival of Words, Perth, 26 April 2024

Frieda Morrison

Frieda was introduced by Iain Mackintosh, chairman of the Friends of William Soutar, who thanked his namesake Jim for issuing the invitation on behalf of the Friends.

Frieda described her work as a BBC radio producer and presenter, highlighting the award-winning Scots Radio programme which portrayed the use of Scots throughout the country in daily work and play. We got a reading from a well-thumbed copy of Seeds in the Wind as a bonus! Frieda also made use of sound and video clips to highlight the extent of her coverage.

Frieda is also a talented musician, singer, composer, film and documentary maker. She was passionate about the importance of preserving the history and culture of all parts of Scotland, particularly her native north-east, where she chairs the Doric Board, currently running 79 projects!

Frieda has been honoured by many Scots and international bodies. She is an ambassador for Creative Scotland, Aberdeenshire, Education Scotland, the Scots Language, and runs Birseland Media, a multi-media company.

Exploring the Links between Soutar's Bairnrhymes and today's resurgence in Scots

The Soutar Festival of Words, Perth, 28 April 2023

James Robertson

James was introduced by Jim Mackintosh, secretary of the Friends of William Soutar, who had issued the invitation on behalf of the Friends.

James delivered a fluent and comprehensive address to a large audience, both in the Soutar Theatre and also online via Zoom. He read widely from the Bairnrhymes, remarking on their originality, their diversity of subject matter and settings, their use of Scots, their humorous twists, and their darkness and light.

The relationship between Soutar and Hugh McDiarmid was explored and James convinced us that it was genuinely friendly and respectful, if subject to occasional contumacious interludes. They remained kindred spirits throughout their association.

Changes in language though global media influences have prompted James to publish a series of Scots poems via his Itchycoo imprint, and we were treated to a range of these - street savvy and very funny!

Approaching William Soutar

A talk for the Friends of William Soutar, at the Soutar Festival of Words, Perth, 23 April 2021

Alan Riach

Alan Riach

Professor of Scottish Literature

Glasgow University

I am so grateful to have the opportunity to say a few words in this Festival of Words about William Soutar, and I should begin by thanking Ajay Close, who invited me, and Iain Mackintosh, Kirsty Brown and Douglas Scott, who are looking after us all and hopefully saving me from my technological incompetence.

I mentioned to Iain that I was looking forward to this evening with a mix of eager pleasure and the respectful trepidation I feel when I talk to Burns specialists who always know more than I do. I hope you'll forgive my inadequacies but I'd like to emphasise that I'm grateful mainly to have had the chance to reread William Soutar and remind myself what a fine poet he is. Of course, given my own history of involvement with the phenomenon of Hugh MacDiarmid, I'm hypersensitive to the question of the relationship between them and the vexations that have been prompted by MacDiarmid's use of the word ‘minor’ in the least inoffensive location, the introduction to Soutar's misentitled Collected Poems. We can concur immediately that MacDiarmid could be unpleasantly wild sometimes and more given to provocation than fairness and exactitude in his work as an editor. Nevertheless, I'm going to try to disentangle a few things about this question and draw out what I take to be the central fact of the relation between these poets and something we all of us — friends of Soutar, advocates of MacDiarmid and contagious carriers of the healthy virus of Scottish poetry, the arts in general and the Scots language — hopefully, can agree on. I'll aim to come back to this in my conclusion.

I should also begin by promising an ending to my talk which I hope will open into a conversation, first with two friends and colleagues whose work on Soutar deserves some further appreciation than it has been given, and whose approaches to Soutar were very different from my own.

And talking of approaches, I should begin properly now by fulfilling the promise of my title: ‘Approaching William Soutar’. I'll do that first in personal terms and then in a moment look at his place in modern Scottish poetry more generally, then close in on a few single poems before opening out again at the end of my talk.

I was born in Scotland, in Lanarkshire, and my father was born in the far north, in Dingwall, and he grew up in the Western Isles and trained as a cadet in the Merchant Navy and like William Soutar he went to sea as a young man, so when he became a Trinity House Pilot on the River Thames we moved to England and I went to school in Kent. And that was where I was first introduced to Soutar's work, when I was in my final year at school, preparing to go to Cambridge University to study English literature.

My headmaster pointed me in the direction of MacDiarmid. ‘You should know about this poet,’ he told me. ‘You're Scottish, you're from Scotland, and this is a poet living now who has been writing in the Scots language and is a great modern poet. You should know about him.’ Also, I had a teacher with whom I studied Robert Henryson's Testament of Cresseid, for the Cambridge entrance exam, and I did so in the slim little Penguin edition edited by MacDiarmid that had only just been published. This was in 1976, in the last years of MacDiarmid's life. So between my school headmaster and teacher and in such an unlikely location as Gravesend, in Kent, surrounded by such very different voices and sounds as the south of England generates, and Joseph Conrad and Charles Dickens as more familiar literary company, I started reading MacDiarmid. And later I met him, hitchhiking overnight from Cambridge to Edinburgh and meeting an uncle of mine who helped with a car and I went over to Biggar and visited the poet, and I read the collection Scottish Scene, by MacDiarmid and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and found the poem ‘Tam o' the Wilds and the Many-Faced Mystery’, which MacDiarmid dedicated to Soutar, and so I went looking for Soutar's poems, and then they came into my reading, and they've stayed, a satellite in the firmament, ever since.

MacDiarmid's poem to Soutar is a rarity: it's his only narrative poem and for most of its length the portrait of Tam is its centre: ‘Tam was a common workin' man, / Or, raither, an uncommon ane; / An eident worker a' his days, / In his scanty leisure a roamin' ane.’ Tam has a loving and supportive family life, works with dedication and punctuality, but every minute of his time not spent with work or family he is completely committed to learning at first hand everything he can about the natural world.

What man in his sober senses 'ud set

Cases o' preserved spiders and pickled snails

Roond his cottage wa's insteed o' a picter

O' His Royal Highness the Prince o' Wales?

It shouldna be allowed. That's a' that's aboot it.

Let him think instead o' the Wrath To Come.

He'd better spend his time on his bendit knees…

Tam's unique enquiry into the world and his developing understanding of it is the poem's subject:

Every wave o' the sea, every inch o' the land

Was fu' o' a thousand ferlies to him

That no' a'e man in a million ever sees.

A familiar tone of scornful disdain for the preference for self-satisfied ignorance most people seem to espouse seems to merge MacDiarmid's voice with Tam's righteous understanding of the value of knowledge: ‘“Waste your lives, fools, in needless sleep. / Nature at least is never at rest!”’. And MacDiarmid indulges his predilection for lists of obscure and wonderful things as he itemises Tam's ever-expanding knowledge:

Wha kent ocht o' fish alang that grey coast [Morayshire]

Save herrin' and haddock and cod and a wheen mair

That folk could eat — the only test applied?

Tam saw and studied day after day there

The Sandsucker and the Blue-striped Wrasse,

Six kinds o' Gobies, the Saury Pike,

Yarrell's Bleny, and the Silvery Gade

(Lang lost to science), and scores o' the like.

MacDiarmid elaborates his account of the autodidactic Tam over nearly ten pages but then suddenly performs an astonishing refocusing in the final four stanzas of the poem, turning directly to Soutar himself:

I had written this and I suddenly thocht

O' ane withdrawn frae the common life o' men

Shut awa' frae the warld in a sick-room for aye,

Yet livin' in what a wonderfu' world even then

— The pure world o' the spirit; less kent

To nearly a'body than Tam's interests even

And I saw in his sangs the variety o' creation

Promise in a new airt mair than a' he was leavin'.

A Scotsman o' a faur rarer type

Than Tam o' the Wilds, and still mair needit,

Tho' still less likely than Tam's kind even

By the feck o' oor folk to be prized or heedit…

And that's the point: the wonderful, praiseworthy Tam, learning through his own untiring efforts out in the world, is a counterpoint to the equally miraculous William Soutar, an exemplary human being, in MacDiarmid's view, shut away from the world but revealing in his songs the diversity of all creation. Reading that poem, I've never been able to doubt the quality of MacDiarmid's friendship, respect and love for William Soutar. To both poets, as with Tam, the real world is discovered by the autodidactic principle of investigation and practical application. MacDiarmid learned this in his four years as a soldier, from 1915-19 and Soutar in his two years as a naval man, 1917-18. Both worked hard to achieve a microcosmic understanding of universal realities, prompted by their experience of the First World War and then fascism in Spain, and then the Second World War. Both knew that something better had to be created than the worlds that made possible and fuelled these devastations.

Now I'd like to think of Soutar in the landscape of modern Scotland and modern Scottish poetry.

Let's propose four stages in modern Scottish poetry:

- Post-1922 in the aftermath of the First World War, Hugh MacDiarmid generates a vision of the multiple, indivisible nation from Dumfriesshire to Shetland: Scotland, comprised of three forms of identity, the Gaelic word, dùthchas, that is land, people, culture —

- Post-1945 in the aftermath of the Second World War, the Seven Poets generation arises, all men, all with favoured territories, geographies, from Orkney to Edinburgh, Lochinver to Glasgow, Skye and Raasay to Lewis —

- Post-1970: Liz Lochhead marks a break-through with her first book Memo for Spring (1972) and an increasing number of women publish significant poetry, including Meg Bateman, Kathleen Jamie, Gerrie Fellows, Jackie Kay, Anne Frater, and the network of relations between individuals, affinities of language, place and the nation are revised again —

- And then increasingly since 1990 there is the alteration of context: publishing poetry in a culture less print-based than based in online Information Technology; and developing along with that there is an awareness of Ecopoetics: climate crisis, environment, the meaning of ‘nature’ and the wilderness.

Now, each one of these stages builds on the past, although it may begin as a break with the past. Not one of the poets of each ensuing generation is in any sense a disciple of anyone who went before, but all of them recognise gratefully what they've learned from their predecessors, selectively, of course. That's partly because each new generation has bequeathed legacies that later generations can learn from gainfully. So where does Soutar fit in this scenario?

Soutar's singular place arises in that first stage, and his legacy is threefold:

- in the Scots lyric poems of loss, loneliness and love, so given to song and interpretation beyond the book;

- in the Scots poems for children, so enlivened by verbal dexterity and delight, quick-wittedness, a sense of fun alongside gruesome threatening danger; and

- in the restraint of the English poems of distanced witness.

Like MacDiarmid, the potency of Soutar's legacy continues but also, like MacDiarmid, it has been badly eclipsed in our educational system, our media and our channels of cultural control. The language we call Scots has had to be and continues to have to be fought for, at least as much as Gaelic. Neither are given the liveliness they demand by our cultural gatekeepers. Of course funding is required but far more important is fun. As William Carlos Williams says, ‘If it ain't a pleasure, it ain't a poem’, and all Soutar's bairnrhymes and whigmaleeries are joyful. Eldritch or tickly they all are made lively by glee. But how many of our teachers shy away from the Scots language? Why are some folk always complaining about Scots along the lines of, it's not a language, it's just a dialect, or slang, or bad English? These people should get help.

Why not just have some fun with it? ‘It's a braw bricht munelicht nicht the nicht!’ — Aye, fine, and:

There isna onie simmer

That winter winna blae:

There isna onie kimmer

Wha's roses dinna grey

The fiddle and the fiddler

Canna be aye jocose:

But hae ye met Tam Tiddler,

And hae ye seen his nose?

And Bawsy Broon's oot there in the nicht, waitin for the gormless chiel tae wander owre the muir, and there's lauchter in the munelicht and trembling in the grun, and gin ye walk on yon shoogly muir, ye'll hear the eldritch croon: and ye shuldna gang oot in the nicht, och, dinna gang oot in the nicht, for Bawsy Broon is oot there waitin, lauchin and lowpin aroon, and lowpin aroon, and gin he gets near ye, weel, ma wee frien, there'll be somebody grippin ye, nippin ye, trippin ye, somebody haudin ye, ticklin ye, kickin ye, somethin that's no tae yer likin'll lippen ye — and that'll be Bawsy Broon —

Now that isn't William Soutar's poem, ‘Bawsy Broon’ but I was reading it and I found myself carried away by its effervescence, its high spirits, the fun of its linguistic dexterity and sinister comicality, and that paragraph just spontaneously combusted itself onto the screen!

Before that is the second verse of Soutar's 1941 ‘Whigmaleerie’ poem &lasquo;Tam Tiddler’: just savour the way the tone swivels like a Scotch snap in music, from the first proverbial wisdom in two lines, through the following one in the next two lines, and the third with its slowing down in the awkward twist of consonants and vowels in the third-to-last line, and then the massive release of shared astonishment and judgement in the last two lines, with the heavy emphasis of weight on each one of the last three words of the last line. It's as if the sounds themselves, the musical tones of the language, not their volume but their power, are telling us that this is well-known, and that is familiar, and this next truth is self-evident, but HAVE YOU SEEN THIS? AND EVEN MORE — THIS! Spelling it out like that is all very well but the fun is in the saying of it.

So let the lesson be to show respect through our irreverence. There is no sacred text but life itself.

I love the Scots language for all its velar fricatives!

I love it for its body-ality, the way it keeps you aware of your muscles and throat and saliva. Mind and body are not separate. When heart and brain are not connected, dear persons, you're dead.

I could happily talk for hours about Soutar's poems in Scots for adults and children, but since his poems in English are relatively neglected I'd like to dwell on a few of these.

Some were published early on by MacDiarmid — or rather C.M. Grieve — in Northern Numbers, Being Representative Selections from Certain Living Scottish Poets, Third Series, edited by C.M. Grieve (Montrose: C.M. Grieve, December, 1922). Soutar is one of twenty contributors: ten men, ten women — MacDiarmid's editorial policy demonstrating his proto-feminism. He is represented by three poems: ‘Invocation’, ‘The Slayer’ and ‘Daphne’. The texts are reproduced below as Appendix 2. As far as I can see they have never been collected in any of the editions of Soutar's poems but they have considerable value when we look closely at them, perhaps less in themselves than as indications of central themes in Soutar's imagination that would find finer expression in later work.

‘The Invocation’ repeats through four stanzas the evocation of ‘Sabbath bells / Over all the chapels pealing’ and ‘Sabbath songs / Over all the champains straying’ from ‘eager throngs&rquo; to ‘the holy hermit praying’ and ‘Sabbath prayers / Over all the churchyards sighing, / Winding down the earth-clung stairs’ into ‘the dust of sleepers’, and finally the Sabbath bells once again, ‘Far within my tired heart calling’ to ‘my sinking soul’: ‘Three for love and two for pain: / Jesus Salvator Nazaren.’

‘The Slayer’ begins with ‘A noiseless flight o'er the starlit sand’ and a series of mysterious sounds and movements, external and internal, starlight, ‘wailings’, blood pulse, shadows and moonlight, the winding stream of Jordan and the gleaming ‘sacred city’ where the ‘hot tears’ of God ‘sear his face’ as ‘the children laugh and play’ and ‘a broken thing falls deadin its place of refuge’. The logic is undefined but the imagery presents the narrative of the securities of Christianity destroyed, innocence made vulnerable, a hope of refuge is turned into a mausoleum or a field of slaughter. It's a sinister poem where vagueness is a threatening imposition.

‘Daphne’ evokes the transformation of the woman into a tree, most wondrously depicted at the end of Richard Strauss's 1937 opera as she is heard and seen ‘returning to the leaves and mountains’ while ‘Gods of dimmer meaning’ are ‘mystically gleaning / Deeper words and kisses.’ Daphne leaves ‘Spring's wild riot’ for the ‘hopes and fears’ of ‘Twilight in the forests where the dead leaves hiding / Hear no more the chiding of thy pearly tears’ and ‘Gods of passion’ begin to lose themselves, ‘mystically choosing / Deeper words and kisses.’

Imagery drawn from both Christian and pagan myths, images of death and despair, tender vulnerability and an inward-turning affiliation between human and natural worlds, tears on the face, leaves on the branches, bells tolling in an expanding air, music, yearning and sorrow crossing fields of the Scottish countryside and expanses of the questing mind, the night sky, stars and loneliness. Each poem has a haunting effect or enacts a haunting experience, counterpointing a solitary person in the midst of the experiences the poem evokes, and a multitude of contexts surrounding him, or her. The contexts are religious, public and social but also seasonal, natural and intimate. All involve transition, loss, the prospect of possible renewal set in an atmosphere of contingency and uncertainty.

And this gives us some indication of Soutar's practice of counterpoint, the dual directions of his mind and writing: not only English and Scots but also English Latinate precision applied to Scots vowels normally sounded in elision, and the richness and delicacy of Scots applied to normally Latinate English syllables; not only ‘Into a room’ but also ‘Out from it’; not only an inwarding but an outwarding too. His life has often been seen as a series of recessions, a deepening introversion but it is perhaps better understood as fivefold: childhood and youth, 1898-1916, at war in the Navy, 1917-18; student life at University, 1919-23; maturity, 1923-30; and the room, 1930-43. The particular extent of the introspection his later life made possible gave him an extraordinarily singular position from which to engage vicariously with the active, international and intellectual adventures of his earlier life. The virtue of this is the authority of centrality in his position as a witness and judge. In the film clip we'll see later, MacDiarmid accuses him of being ‘in the middle’ — and in a sense that's a rare virtue for a poet. And Soutar made all that he could of it. His work has always seemed to me not so much increasingly inward but rather like rings on a tree, endorsing its own self-possession and self-determination while travelling outwards into the world, or even better, working like a sonic radar, picking up traces, hypersensitive as bats' ultrasound, emanating into the public and political world and then returning to the solitary sensitivity, with its singular moral social precepts, its priorities of Christian justice, fairness, restraint and kindness, an aptitude for generosity and optimism, and hence a care for children, particularly. Children are an essential component of Soutar's sensibility, and in this he is quite unlike MacDiarmid or any other of his contemporaries and much closer to Robert Louis Stevenson.

The biography delivers a keen, quick sense of his apprehension of the physicality of childhood, both his own athletic prowess as a boy and young man, and the imagination at work in his writing, which is what connects him to Stevenson. The deep, constant question for Soutar was: How to teach children? How might poetry appeal to a sensual apprehension of wee things and glee? The energy of childhood is about size: not magnitude but speed, not presence but the abilities that come with a knack for concealment, like young Jim Hawkins in the apple barrel, in Treasure Island. The whole plot of that novel and the essential moral difficulty it presents to us, that Jim must learn that Silver is not only a mysterious romantic magical figure, he is also a brutal murderer capable of extreme violence — all these things depend on that crucial moment when Jim is small enough to hide in the apple barrel and overhear the adult world around him. So what does Soutar, from his place of ostensible retirement, hear of the world beyond? The garden beyond is full of living things, like Maurice Ravel's child in his wonderful little operatic masterpiece, L'enfant et les sortilèges (1925). Ravel's child experiences a world where flamboyance, personalities, errant emotions and didactic moral intent leavened by irony are all imbued with magic. This is a world in which cruelty is enacted and must be atoned for. Like Ravel, Soutar listens and looks, acutely, and he records and writes his findings down, but his work is more than witnessing. It is also judgement. Being accurate to the world he senses, even if he cannot physically participate in it, does not diminish but enhances the acuity of judgement. And the judgement is measured by the vulnerability of children. And that vulnerability is measured against the appetite of children for the size of the world out there. That balance, that counterpoint, is what gives Soutar's best work its tension and energy.

This is not easy or comforting. It is familiar with violence and nightmare, mystery and the dance, and the dance can be joyful or macabre. Speed in your movement and security in rest and repose are essential to well-being, most necessary in childhood. The freedom of the body and its opposite, enclosure, entrapment, confinement, constraint — both counterpoints are there in Soutar's best work. And when freedom becomes intoxicated with its own energy, Dionysiac dangers are unleashed.

This point of view, afforded by the potential inherent in the Scots language, allows a particular strength to inhabit its vision. In that vision, the single priority of authority is that it must be protective of the vulnerable. Young and old people, in any domestic circumstance, the family, the village, the small town, but then beyond, in an international context, the world, experienced through journeys, across oceans: the most vulnerable need the protection of adults. Soutar lived through the exuberance of youth and in the Navy, his experience of the structures of power were acute: the purpose of command and the meaning of duty were as essential as any Christian virtues. But then there is the other side. The abhorrence of war, the horrifying fact of Guernica, what fascism means in its literal enactment, the slaughter of innocents, and the exercise of tyranny. And this has its bearing on his poems not only in Scots but also in English.

The best characteristics of rural Scotland, a farmers' world of villages and small towns, or village cities, like Perth, include camaraderie, such as might be imagined in the Navy, both companionable and professional, carried through by solitary responsibility. So the biography is indeed significant not as a martyrdom but rather as a unique provision, a price paid, at great cost. If you see Soutar's life chronologically in five periods contemporaneous with the major revolutionary and violent political movements of the first half of the twentieth century his ‘middle-ness’ or ‘centredness’ is clear. This is sketched in Appendix 1.

The poet's work — any poet's work — is most often dominated by one of two perspectives and roles. He or she is a revolutionary, making an intervention, attempting to change the world. Or else, he or she is a witness, observing as closely, astutely and accurately, making elaborate comment superfluous by simple indication. These two roles are not exclusive of each other but they are different. Soutar, in his Scots bairnrhymes and whigmaleeries, attempted an intervention. Our educational establishment and the obedience of elders to the rules of the Queen's English have by and large stopped that from taking effect. His poems in Scots for adults, poems of unmatched pathos and poignancy, have their permanent appreciation amongst all who have read them, no question. His poems in English, the disinterested observations packed with understated or even unstated compassion, are relatively neglected, so I'd like to pause on a few of them now.

To the Future

He, the unborn, shall bring

From blood and brain

Songs that a child can sing

And common men:

Songs that the heart can share

And understand;

Simple as berries are

Within the hand;

Such a sure simpleness

As strength may have;

Sunlight upon the grass:

The curve of the wave.

(1937)

The three worlds, of the dead, the living and the unborn, are called up and held in balance in Soutar's work. The Scots and English languages both draw upon voices long dead, generations gone, but they are living tongues; the living learn such things as help us now to live, how to live, and what we need to honour the dead and prepare for the unborn. That's why children were so close to Soutar's mind and sympathy. In Gaelic mythology the land of the dead is also the land of the ever-young. Generations past and still to come both inhabit an immaterial world, surrounding but beyond those who are now living.

The bombing of Guernica, in Spain, took place on 26 April 1937; there was an eyewitness account by George Steer in The Times> and The New York Times on 28 April; and Picasso made his famous painting, Guernica, and it was first seen in June 1937. Now, I am indebted to Paul Philippou for this reference: in a letter to George Bruce of 27.4.42, Soutar writes: ‘No doubt you saw “The Children” in The Adelphi — Max Glowman asked if he might print it after having seen the selection. I wrote it in 1937 with the bombing of Spanish civilians in mind: it has appeared in quite a few places since.’ (National Library of Scotland MS.8787 Correspondence with George Bruce, 1941-43). I had associated the poem with Guernica but was sensitive to the universality of its terms and wasn�t certain that it could be specifically linked. This reference suggests that whether or not it was written in the wake of that atrocity it applies more widely. And that underscores what I'm trying to say about Soutar's understanding and sympathy with the vulnerability of children, although the letter to George Bruce doesn't exclude Guernica from its judgement.

The Children

Upon the street they lie

Beside the broken stone:

The blood of children stares from the broken stone.

Death came out of the sky

In the bright afternoon:

Darkness slanted over the bright afternoon.

Again the sky is clear

But upon earth a stain:

The earth is darkened with a darkening stain:

A wound which everywhere

Corrupts the hearts of men:

The blood of children corrupts the hearts of men.

Silence is in the air:

The stars move to their places:

Silent and serene the stars move to their places:

But from earth the children stare

With blind and fearful faces:

And our charity is in the children's faces.

(1937)

The universality applies to this next poem also and it's perfectly brought out in the piano setting by F.G. Scott, available on the CD Moonstruck (Signum Classics sigcd096, 2007) with Lisa Milne (soprano), Roderick Williams (baritone) and Iain Burnside (piano). In Scott's setting, violence and pathos are held in a balance only realisable in music. However universal it is, however, the poem's date gives us the context of the Second World War and the rise of fascism in Europe and the tyrants, the dictators, who led that movement, and that makes its universality horrifically pertinent to its moment of composition. It is no less pertinent in 2021.

In Time of Tumult

The thunder and the dark

Dwindle and disappear:

The free song of the lark

Tumbles in air.

The froth of the wave-drag

Falls back from the pool:

Sheer out of the crag

Lifts the white gull.

Heart! Keep your silence still

Mocking the tyrant's mock:

Thunder is on the hill;

Foam in the rock.

(1938)

All the books that have collected Soutar's poems over half a century to some extent impose ways of reading that take readers away from the biography. Their contents are most often categorised by language and genre, not by order of publication, let alone order of composition. W.R. Aitken supplies dates within sections, but this does not show how contemporaneous were his compositions in English and Scots, and his poems for children as well as for adults. The important point here is that if we read the poems within the biography we can see clearly that there was no ‘conversion’ from English to Scots or from adult to children's poetry. All his poems form parts of a complex continuity.

And they lend themselves to music. As lyric poems their singularity is crucially inherent to voice and movement, pace and tone, imagery and symbolism, and the extent of the success of each one is measured by the extent of its rejection of singularly detailed autobiographical particularity, the exceptionalism that leads directly to sentimentalism. Each one of the best of them is an exercise in crafted attention to universal application sharpened by the historical moment, made cutting, scarifying. In this respect, their closest affinity is with the Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794) of William Blake.

And there's nothing minor about that.

I'd like to draw towards a conclusion now with the film, The Garden Beyond, which is to be shown in its entirety as part of this festival later on but here hopefully we'll watch a short clip from it and try to draw together the idea of ‘Approaching William Soutar’ by virtue of that.

The Garden Beyond (released 1 January 1977; running time 60 minutes; Bertie Scott as William Soutar, Henry Stamper as Chris Grieve or Hugh MacDiarmid, Bill Paterson as Jim Finlayson; writer: Douglas Eadie; director: Brian Crumlish) is a dramatised portrayal of Soutar's life from the point of view of his later years, when he was confined to bed. Made in 1977, it was the first independently produced Scottish film to be broadcast on the BBC One UK network. It reflected, as well as Soutar's own passion and commitment, the debate about Scotland then current in the run-up to the 1979 devolution referendum. Would that it were shown every year on Soutar's birthday, 28 April, on the UK BBC! It might enhance a better understanding of Scotland's distinctive national cultural identity and reach a broad audience who are otherwise given so little opportunity through mass media to encounter our country's culture and riches.

The extract from the film we're hopefully about to see is an exchange between Soutar, played by Bertie Scott and MacDiarmid, or Chris Grieve, played by Henry Stamper, and I wanted to spend a few minutes with this because it shows far better than my words can possibly do the nature of their friendship. This is conveyed in the sparring and the laughter, the emotional undercurrents of warmth, recognition and acknowledgement, the sense of common purpose alongside the distinctions of priority, the differences between them.

We begin with Chris reading from a late, long poem, almost incomprehensible in its demands of syntax and vocabulary and the contrast with Soutar's ‘lyric humanity’ is keenly observed. This isn't just the academic exercise, ‘compare and contrast’ but an evocation of friendship and an argument that was lived: seriousness and irony, sympathy and judgement are all in play.

After MacDiarmid's list of languages, Soutar's question, ‘What is it in Gaelic?’ is a wonderful reductio ad absurdum, matched by Grieve's answer, ‘Irish stew!’ The balance of jokiness and deadly meaning is held in balance. Soutar says sadly how far MacDiarmid's ambitions are from his lyric idea and the corrective comes, ‘We're not in a lyric situation any more,’ and ‘Don't be ordinary, Soutar!’ Grieve advises. MacDiarmid's ambition is to do for literature what Lenin has done for politics, he says. And Soutar brings him down with, ‘You're a poseur, Chris.’

I love the badinage between them, the way they use last and first names to address each other, so accurately depicted, in affection and in warm reprimand. When MacDiarmid says that he sees Scotland as a tiger gathering its strength for a great leap forward into the future, free of capitalists and above all free of ‘English imperialist domination by mediocrity and damned coldness of spirit’ you can feel the passion slipping between the command of the epic poet, the bard, and the insight of the sympathetic mortal man. It's wonderful to have MacDiarmid say that he considers Soutar ‘one of the bright sparks’ and Soutar respond: ‘The fire I'm lighting is in a nursery — bairnrhymes’ — he says it's a long way round to the new Scotland but safer than bloodshed and revolution. And then there's MacDiarmid with his back to Soutar, looking out through the same window, onto the domestic garden. ‘Homer is normally thought of as blind,’ he says. What does he mean? That more can be seen by those whose view is so badly impaired?

Then Soutar tells the parable of his dream, that the two of them had been in contest over a cigarette — and in a brilliant piece of filmmaking, the contest over the cigarette is enacted and resolved in real time over this part of the film — but the dream is of two fighter planes firing machine-guns at each other. Soutar says that in the dream, MacDiarmid's wife, Valda, appeared, and spoke of the destruction of ‘the flags and the greenery’ — nationality and nature — and Soutar praises her: ‘It took a woman to see it.’

But MacDiarmid will have none of this: ‘I'll have nothing to do with your damned humanism — the spark of humanity?’ (the imagery picks up from lighting the fire in the nursery) — he calls this ‘sheer sentimentality! Look in the eyes of a man who has been unemployed for half his life’ — he's ‘a human slum’ and the slums must all be brought down, demolished. MacDiarmid is thundering. For him, the past must give way. But Soutar's faith stays in building out of the past. Passion and patience are equally matched.

Whose side of the argument elicits your sympathy, as you watch this? As each man speaks, commitment and political will are engaged by both, contagiously. Soutar's reply is mocking: a new red Scotland, strong as steel, is more likely to be no more than a heap of pig iron. MacDiarmid's talk is ‘Blethers!’ Soutar's commitment is different: renewal through ‘uncoercive, non-violent acts is my position.’ MacDiarmid dismisses that: ‘Sounds like Patience Strong to me.’

Incidentally, just for information, Patience Strong was the pseudonym of Winifred Emma May (1907-90) who wrote popular daily poems in The Daily Mail from 1935 through to 1946 and then in the Sunday Pictorial, The Sunday Mirror and Woman's Own and This England magazines. Such poems were intended more for pious recitation than revolution.

And then the film brings us to the final counterpoint: Soutar characterises MacDiarmid as the extremist, where extremes meet, Nationalist, Communist, Borderer, Shetlander. MacDiarmid returns the compliment of insult: Soutar is a middle-man, in middle-Scotland, middle-Earth, in Perthshire, in the middle. And the two of them are laughing — and, beautifully, sharing that last cigarette.

Soutar's father comes in and when the poet introduces MacDiarmid as the man who would wish to have engraved on his headstone the words, ‘A disgrace to the community’ his father's patient sigh is wonderful: ‘It tak's a' sorts…’ He brings a question from Mrs Soutar about whether Grieve will be staying for his tea. MacDiarmid's acceptance is polite, quick, sly, and surreptitiously eager, and dismissive, as he goes back to the poems, ‘moving towards immortality by mortal roads.’

If we see the film as a depiction of a moment in history and think back to the historical evolution of Scottish poetry I talked about towards the beginning of my lecture, we can see how the conversation foreshadows aspects of what was to follow. In Soutar's sketch of MacDiarmid as a poet of extremes, from the Borders to Shetland, there is that national configuration, and in MacDiarmid's caricature of Soutar as a middle-man in middle-Scotland, we can see both the encompassing of a multi-faceted national identity and the emphasis upon a particular favoured place, a poet's preferred territory, which would characterise the post-Second World War poets. And in the oblique reference to Mrs Soutar preparing ‘the tea’ we might wonder what she would have to say for herself if she were given to writing poems — not of the Patience Strong variety. In the generation of Scottish poets working since the 1970s, that too has been brought into being.

But it's time for me to be quiet and watch the film.

Excerpt from The Garden Beyond by Douglas Eadie

What this film clip encompasses, then, is a brilliant portrayal not only of the two poets but also of their relationship, as well as their sense of what's at stake in the world they inhabited: Scotland, literature, poetry, languages, the arts, lyricism, Empire, fascism, oppression and revolution. What they believed should be brought into being, what they were committed to, what they helped to create. And when I look around at Scotland in 2021 there is no diminishment of urgency.

For what is the community of purpose they defined, that's visible, so palpable in this film?

All talk of a supposed rivalry, the minor poet question, who is Major Minor? — is an absolute distraction from the bigger purpose both these poets were committed to.

Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham could be described as a minor writer compared to his friend Joseph Conrad, Christopher Marlowe compared to William Shakespeare, and Mark Alexander Boyd only wrote one poem in Scots but it's a major work by any reckoning, the finest sonnet ever written, according to Ezra Pound. You can see its opening lines on the Royal Bank of Scotland £20 note. The film clip is full of quick turns and shuffled meanings, metaphors and power. And the most powerful metaphor at work here is Scotland. For Soutar, in poems like ‘The Unicorn’, ‘Three Men of Scotland’ and so many others, and more broadly in his deployment of the Scots language, the fire sparked up in the nursery was as essential as MacDiarmid's ‘major’ revolutionary programme. Both have been consistently opposed. Their enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

So the most essential point of all is to see the value in both, not in one above the other, not the two made separate, in contest, but in the company they kept, the dead they honoured and brought to good use, the readers they addressed in their lifetimes and after, in the legacy that remains quick and vital, and for all of us, what the common purpose is.

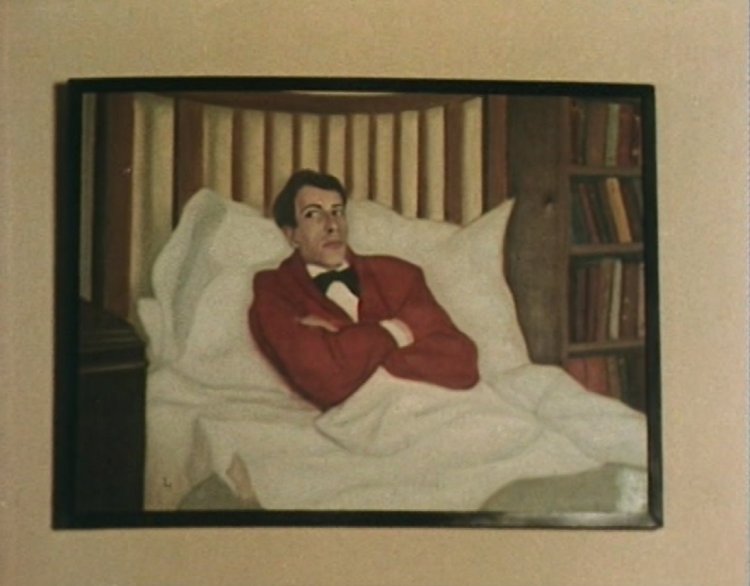

Portrait of William Soutar by Alexander Moffat

Sandy's portrait of William Soutar gives him his own place, outside of the company collected in his great painting ‘Poets' Pub’ but of an earlier era anyway, and looking askance, across it all, critically, at past and future both, as well as considering his present condition, wonderingly, hopefully. His solitariness, solitude, irony, his avoidance of self-pity, his sense of humour and his valuation of friendship and support, are essential. Their purpose is redress, to correct a lack of giving, to give, and he gave.

[Alan then invited comment from Douglas Eadie, film-maker and Alexander Moffat, artist, who talked about their roles in creating The Garden Beyond and the portrait of Soutar and their respective approaches to the poet, then further conversation and comment was opened to those attending the event.]

Appendix 1

William Soutar: biographical timeline

BIO 1: 1898-1916: born, goes to school in Perth

1914: Start of WWI

1916: Easter Rising, Ireland

1917: Russian Revolution

BIO 2: January 1917-December 1918: in the Royal Navy

1918: End of WWI

BIO 3: 1919-23: at Edinburgh University

1922: Civil War in Ireland

BIO 4: 1923-30: in his maturity

1926: Foundation of the National Party of Scotland

BIO 5: 1930-43: in the room

1934: Foundation of the Scottish National Party

1936: Spanish Civil War

1937: Guernica

1939: Start of WWII

BIO 6: 1943: dies

1945: Hiroshima, Nagasaki; end of WWII

Appendix 2

Hugh MacDiarmid — or rather C.M. Grieve — edited Northern Numbers, Being Representative Selections from Certain Living Scottish Poets, Third Series (Montrose: C.M. Grieve, December, 1922), in which Soutar is one of the twenty contributors, represented by three poems: ‘Invocation’, ‘The Slayer’ and ‘Daphne’.

Invocation

Sabbath bells, Sabbath bells

Over all the chapels pealing,

Creeping through deep hidden cells

Where the pious beadsman kneeling

Hears, and counts his beads amain

Three for love and two for pain:

Jesus Salvator Nazaren.

Sabbath songs, Sabbath songs

Over all the champaigns straying,

Rising from the eager throngs

Till the holy hermit praying

Hears, and chants his prayers amain

Three for love and two for pain:

Jesus Salvator Nazaren.

Sabbath prayers, Sabbath prayers,

Over all the churchyards sighing,

Winding down the earth-clung stairs

Where the dust of sleepers lying

Stirs, and counts the years amain

Three for love and two for pain:

Jesus Salvator Nazaren.

Sabbath bells, Sabbath bells,

Far within my tired heart calling,

May there be no sad farewells

When your deep-ton'd numbers falling

Drowse my sinking soul amain

Three for love and two for pain:

Jesus Salvator Nazaren.

The Slayer

Deuteronomy xix, 5 and 6. ‘…he shall flee unto one of those cities, and live: lest the avenger of blood pursue the slayer, while his heart is hot, and overtake him, because the way is long, and slay him.’

A noiseless flight o'er the starlit sand;

A corpse by the starlit stream:

Strange wailings within the saraband

And blood in the high priest's dream.

Ten thousand sounds through the palm grove fann'd

Ten thousand shadows dim.

And the distant beat of avenging feet

As the moon swings over him;

And the cold stars white, as the eyes of night

Pitiless — stare on him.

Pale as the lips of the corse that lay

By the winding Jordan stream,

He sees the curve of approaching day

O'er the sacred city gleam.

(Dear God! the children laugh and play.)

The hot tears sear his face:

But the distant beat of avenging feet

Creeps round this hiding place:

As the great gates swing, falls a broken thing

Dead — in its refuge place.

Daphne

Daphne, Daphne — night and shadows falling.

I no longer calling, I no longer near —

Once again returning to the leaves and mountains,

Moonlight on the fountains, thou must cherish dear

Gods of dimmer meaning, mystically gleaning

Deeper words and kisses.

Daphne, Daphne, leave thy dewy ranges,

Spring's wild riot changes, as our hopes and fears,

Twilight in the forests where the dead leaves hiding

Hear no more the chiding of thy pearly tears

Gods of horror keeping, icy-finger'd, reaping

Frozen words and kisses.

Daphne, Daphne through the daylight cleaving

Aery fabrics weaving to blind the eager eyes.

Vain to chide my coursers, vain to follow after

The echo of thy laughter; the autumn of thy sighs:

Gods of passion losing, mystically choosing

Deeper words and kisses.

Appendix 3

Bibliography

William Soutar, Gleanings by an Undergraduate (Paisley: Alexander Gardner, 1923)

William Soutar, Conflict (London: Chapman & Hall, 1931)

William Soutar, Seeds in the Wind: Poems in Scots for Children (Edinburgh: Grant & Murray, 1933 and London: Andrew Dakers, 1933; revised and enlarged edition 1943;

illustrated edition 1948 [illustrations by Colin Gibson])

William Soutar, The Solitary Way (Edinburgh: The Moray Press, 1934)

William Soutar, Brief Words (Edinburgh: The Moray Press, 1935)

William Soutar, Poems in Scots (Edinburgh: The Moray Press, 1935)

William Soutar, Riddles in Scots (Edinburgh & London: The Moray Press, 1937)

William Soutar, In the Time of Tyrants (privately printed, 1939)

William Soutar, The Expectant Silence (London: Andrew Dakers, 1944; repr. 1946)

William Soutar, Collected Poems, ed. Hugh MacDiarmid (London: Andrew Dakers, 1948)

William Soutar, Diaries of a Dying Man, ed. Alexander Scott (Edinburgh: Chambers, 1954; repr. 1988; repr. Canongate Classics, 1991)

Alexander Scott, Still Life: William Soutar 1898-1943 (London: Chambers, 1958)

William Soutar, Poems in Scots and English, ed. W.R. Aitken (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1975)

George Bruce, William Soutar (1898-1943): The Man and the Poet, An Essay (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 1978)

Wiliam Soutar, Poems: A New Selection, ed. W.R. Aitken, (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1988)

Joy Hendry, ed., Chapman 53: On William Soutar (Volume 10, no.4, Summer 1988)

William Soutar, The Diary of a Dying Man [ed. W.R. Aitken] (Edinburgh: Chapman, 1991)

Joy Hendry, Gang Doun wi a Sang: A Play about William Soutar (Edinburgh: Diehard, 1995)

William Soutar, Into a Room: Selected Poems, ed. Carl MacDougall and Douglas Gifford (Edinburgh: Argyll Publishing, 2000)

William Soutar (Songs by Debra Salem, Kevin Mackenzie, Paul Harrison, from the poems of William Soutar), In a Sma Room: Songbook (Perth: Tippermuir Books, 2020)

Musical Settings

Gordon Maclean, ‘Hae ye seen my love’ [Ballad (‘O! shairly ye hae seen my love…’)], &lasquo;The expectant silence’ [‘To the future’] and ‘Sang’ [‘Hairst the licht o'

the mune’] on Just mair snaw, Gordon Maclean, Susan Walker, Barbara Bisset (cassette tape recorded in the Isle of Mull, December 1983)

F.G. Scott, ‘In Time of Tumult’, on Moonstruck: Songs of F.G. Scott, Lisa Milne, Roderick Williams, Iain Burnside (Signum Classics, SIGCD096, 2007)

James MacMillan, ‘The Tryst’, on Tryst: Works for Chamber Orchestra, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Joseph Swensen conductor (BIS-1019 CD, 1999); ‘Three Soutar Settings’:

‘Ballad’ (‘O! shairly ye hae seen my love’), ‘The Children’ (‘Upon the street they lie’), ‘Scots Song’ (‘O luely, luely cam she in’ [‘The Tryst’]), tracks 1, 7 and 13,

respectively, The Shadow Side: Contemporary Song from Scotland, Irene Drummond, soprano and Iain Burnside, piano (Delphian Records, DCD34099, 2011); After the Tryst:

New Music for Saxophone & Piano, McKenzie Sawers Duo: Sue McKenzie and Ingrid Sawers (Delphian DCD34201, 2018)

Debra Salem, Kevin Mackenzie, Paul Harrison, In a Sma Room: from the poems of William Soutar (DSMS1002 2020)

Appendix 4

Hugh MacDiarmid's poem, ‘Tam o' the Wilds and the Many-Faced Mystery’ prompts us to consider the two poets together, and their poems and their working practice in composing their lyrics, in both Scots and English. To both poets, as with Tam, the real world is discovered by the autodidactic principle of investigation and practical application. ‘Tam o' the Wilds and the Many-Faced Mystery’ is about knowledge and wisdom. It creates a character, his family, his working life and class and place in society and in the world. In that respect, it is perhaps MacDiarmid's only narrative poem. But then it compares this character with Soutar himself. And then finally it asks what looks like an unanswerable question, and that question is the poem's conclusion.

‘Tam o' the Wilds and the Many-Faced Mystery’ was first published in Scottish Scene: The Intelligent Man's Guide to Albyn by Lewis Grassic Gibbon and Hugh MacDiarmid (London: Hutchinson, 1934) and is reprinted in Hugh MacDiarmid, Complete Poems, Volume I, edited by Michael Grieve and W.R. Aitken (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1993). It is reproduced here by kind permission of Carcanet Press, Manchester, UK.

Tam o' the Wilds and the Many-Faced Mystery

TO WILLIAM SOUTAR

TAM was a common workin' man,

Or, raither, an uncommon ane;

An eident worker a' his days,

In his scanty leisure a roamin' ane.

He never wasted a penny piece

— Troth, he never had ane to waste! —

He never wasted a meenut either,

But o' ilk ane made the maist.

Early and late he did his darg

And in the wee sma' 'oors atween

Tyauved twice as hard at kittler work.

It seemed he seldom steckit his een.

Early and late he did his darg.

His nose was aye on the grindstane

He couldna been puirer; his hame was yet

In happiness faur frae the hindest ane.

For idle convenin' wi' ither folk

He never had an instant to spare;

He never saw the inside o' a pub,

Or hung aboot bletherin' in the Square,

But lang efter a'body else was in bed

And syne lang afore they waukened again

Tireless he roved alang the seashore

Or inland owre field and forest and ben.

Thinkna' he was ony unsocial chiel

— The test o' that was his wife and weans;

Their happy faces settled a' doots,

Puirest o' the puir yet rich 'yont a' means.

Tam never had a stroke o' wardly luck

But a desperate fecht frae beginnin' to end,

Yet his wife and weans were brawly content

— Their joy ony hand in his ploys to lend.

It was a' the help that he ever got.

For the feck o' folk couldna faddom at a'

A workin' man wi' a purpose in life

'Yont his work and a dram and fitba',

Or mebbies the Kirk, but what could he want

Wi' this passion for nature and science?

It was sheer presumption in a man o' his class

— Settin' human nature, in fact, at defiance!

Set him up wi' his bottles and pill-boxes,

Sea-traps and nets and a' his gear

As if he was an educated man,

When a'body kent he'd neist to nae lear!

It wasna canny that the likes o' him

Should be pokin' his neb night in night oot

Into things that teachers and ministers even

No' to speak o' the gentry kent naething aboot.

Kent naething aboot and, fegs, cared less!

— A' the ugsome vermin o' the laigh creation,

Worms, lice and the like. Certes, the man

Had shairly nae sense o' his proper station.

As for his wife she was if onything waur

Gien' hoose-room to hotchin' rubbish like yon.

Her hoose was a weavin' zoo that gar'd

Ony decent wumman grue to think on.

What man in his sober senses 'ud set

Cases o' preserved spiders and pickled snails

Roond his cottage wa's insteed o' a picter

O' His Royal Highness the Prince o' Wales?

It shouldna be allowed. That�s a' that�s aboot it.

Let him think instead o' the Wrath To Come.

He'd better spend his time on his bendit knees

Lookin' to see if there�s ony �white in the lum�!

The Health Authorities should pit a stop

To sicna ongauns or there 'ud be a plague.

Let the Police act! It fleggit the lieges

To ken that while they slept sic a vaig

Was reengin' aboot, whiles bidin' a' night

Like a beast in a hole in the grun' even.

What was he really da'en? Douce folk

A' thocht it was some sly poachin' or thievin'!

But the years ga'ed by and Tam keepit on

A mystery to a'body aboot'm — Nay

A greater mystery for noo it was clear

Whatever his object it didna pay

He wasna a penny the better for't a',

And wha'd tak' an interest in folly like that?

Naebody gie'd him credit for knowledge even

— Nae honour to the place; a human bat!

Mony an ill gruize he got lyin' oot

A' nicht in snell winds or on water-logged grun',

Gane gyte a'thegither owre his crabs and bandies,

His powets and paddocks, but wadna be done;

Aye thrang wi' black doctors that fulped in a pool

Or wasps' bikes like ba's o' paper hung to a tree

— He�d been a bonny nickem frae his earliest days

And aye got the waur the aulder he'd be!

Yet strugglin' on bawbee by bawbee

His hame was bein 'yont the lave o' his kind

And his bairns like onybody else's bairns,

Weel–fed, weel–pit–on, and didna mind

The sorry esteem their faither was held in

Or the dark suspicions that clung to him still

But in a' their spare time and holidays helped

Mair boxes and bottles wi' bugs to fill.

Whiles a workmate tackled him bluntly and speired

‘What's the use o't a'? — what dy'e hope to get?�

But Tam answered: ‘Naithing, except the joy o't,

And mair knowledge o' wheen things than ony man yet.’

Syne his disadvantages were pointed oot

— Shairly it stood to reason rich and colleged men

Wi' books and apparatus galore ken mair

To stert wi' that he could ever hope to ken?

‘Na', faith!’ said Tam, ‘tho' I'm handicapped

Wi' sair lack o' siller and lear nae doot

It's naething that's in ony book yet

Or money can buy I'm maist fashed aboot.

I've strength and patience and a pair o' gleg een,

And it isna education, riches, or good birth

Advances science maist — else lang syne

A'd ha'e been learnt that's to learn on earth.’

‘But what pit it into your heid ava'

To trauchle wi' this?’ anither speired.

Tam shook his heid: ‘That's no' easy kent

Aiblins the best that I can come near't

Is just wi' a proper reverence to say

The Maker o' a' things made me like this

� And muckle that maist folk think faur beneath

Their notice, certes, isna beneath His!’

‘If ony man has seen onything yet

O' the beauties o' nature in land, sea, or sky,

That's only the merest minimum

O' the glories that await the open eye.

Wherever we turn the haill warld is rife

Wi glories o' hue and design that nae man

Has ever seen mair than the least fraction o'

And nae science has noted, or ever can.’

O few kent better than Tam himsel'

Hoo muckle o' a' God's bothered to mak'

Is beneath the notice and ootwith the ken

O' maist folk and hoo little trouble they tak'

To jalouse and enjoy the riches o' Nature

— He lived in a different warld frae theirs;

The warld God made, and mak's ilka day,

— Completely ootweighin' ony human affairs.

It'd be a meagre and mean creation

Limited to the general interests o' men;

Tho' botany, ichthyology, and a' the rest

Are no for the workin' man we ken,

And for few o' the upper classes even

Except a wheen faddists o' little accoont

— God forbid owre mony like Tam should think

The usual run o' life stupid and soar abune't!

Yet maist folk bogged in clish–ma–claver,

Or, accordin' to their different degrees,

On a solid basis o' dull conventions,

In things o' kirk and State and maitters like these

Miss a million times mair o' the wonders o' life

Than Tam missed gi'en average routine the bye

Night after night up a tree wi' the birds

Or in a badger's hole or eagle's nest to lie.

Every wave o' the sea, every inch o' the land

Was fu' o' a thousand ferlies to him

That no' a'e man in a million ever sees.

Custom mak's creation sae scant and dim

To the feck o' folk, used juist to this or that

And esteemin't accordingly till they canna believe

That a' in and aboot them teems an unseen world

Stranger and bonnier than ocht but God could conceive.

Tam shrank frae nocht born in fear or disgust.

Whaur maist folk scunnered he thrilled wi' delight.

Mere size he kent was naething to gang by.

God spent nae less skill on the obscurest mite

And the man that 'ud follow in the steps o' God

Maun open his hert to the haill wide world

� No' be cut off frae't in ony human rut

Till a' its glories are in vain unfurled.

‘Waste your lives, fools, in needless sleep.

Nature at least is never at rest!’

And sae he kent, when to its mossy bed

The skylark flew and the swallow to its nest

And the mellow thrush its requiem ended

And the wood-pigeon settled doon for the night,

The night jar got thrang wi' its spinnin' wheel

And the moths flew oot for his delight.

The Oak-Egger Moth, the Green Silver–Line,

The lovely China Moth a' were his;

And his helminthology cairried him deep

Into the benmaist dens o' the forest I wis.

Weather was nae bar and mony a wild night

O' lightning and rain and wind he spent

In an auld dyke back or cups in the hills

On the wonders o' nature still intent.

The landrail craiks the haill night through

And a whilie efter sunrise still;

The coot and the waterhen get noisy whiles

In the wee sma' 'oors; a thoosand cries fill

The howe o' darkness — the boom o' the snipe,

The birbeck o' the muirfowl, the plover's wail.

And doon by the sea the ring-dotterel's pipe

And the plech–plech o' the oyster–catcher never fail.

And mony a polecat, stoat, and weasel

Blew on him or hizzed as he suddenly appeared,

And whiles when he dozed in the sea–caves or woods

He was waukened — never in the least bit feart —

By something pit–pattin against his legs

And f'und a rat or a foumart there

Or even a badger as curious as he

To study what this could be in its lair.

Wha kent ocht o' fish alang that grey coast [Morayshire]

Save herrin' and haddock and cod and a wheen mair

That folk could eat — the only test applied?

Tam saw and studied day after day there

The Sandsucker and the Blue–striped Wrasse,

Six kinds o' Gobies, the Saury Pike,

Yarrell's Bleny, and the Silvery Gade

(Lang lost to science), and scores o' the like.

The Bonito, the Tunny, the Sea–Perch and the Ruffe,

The Armed Bullhead, the Wolf-fish, and the Scad,

The Power Cod and the Whiting Pout,

The Twaite Shad and the Alice Shad,

The Great Forked Beard, the Torsk, the Brill,

The Glutinous Hag, the Starry Ray,

Muller's Topknot and the Unctuous Sucker,

— These, and deemless ithers cam' his way.

A cod's stomach for the smaller fry

Was aye his happiest huntin' grund

For testaceous and crustaceous rarieties

— Mony new to Scotland, or even science, he fund —

Fish lice, sea mice, Deid Men's Paps, actinias,

And algae and zoophytes yont number

Were rescued thence and ta'en in triumph

His humble wee but-and-ben to cumber.

And lang by his ain fireside he'd sit

Studyin' an Equoreal Needle-Fish

Ane o' his lassies fund; or watchin'

An anceus or ensirus in a dish

Wi' a care that took in ilka move,

Detail, and habit o' these peerie things,

Soomin' wi' quick motions o' their ciliate fins,

While he coonted and measured spines, rays, and rings.

He heard the corn–buntin' cry �Guid-night�

And the lark ‘Guid–mornin',’ and kent by sight

And call–note the Osprey and the Erne,

The Blue-Hawk and the Merlin and the Kite,

The Honey Buzzard and the Snowy Owl,

The Ring Ouzel, the Black Cap, the Wood Wren,

The Mealy Redpole, the Purple Heron, the Avocet,

The Gadwell, the Shoveller, and the Raven.

He loved the haill o' the countryside

And kent it as nae ither man ever kent

The coast rocks wi' the wild seas lashin' their feet,

And the myriads o' seabirds that cam' and went,

Kittywake, guillemot, razor-bill, puffin,

Whiles darkenin' the air wi' their multitudes,

Wheelin' in endless and varyin' airts

— He kent them singly in a' their moods.

Fishin'–boats shoot oot frae the rocky clefts

In which the harbours are formed — below

The Gardenstown boats and Crovie's to the right,

The fleets frae Fraserburgh eastward show,

Westward the boats frae Macduff and Banff,

Whitehills, Portsoy, Findochtie, the Buckies

— He wishes he was aboard each at aince

Maimin' their nets to see that his luck is!

Far owre the Moray firth the Caithness mountains

Are clearly picked oot 'gainst the evenin' sky.

The hills o' Morven and the Maiden's Pap

A' stand within the scope o' his eye,

And every slope o' hard grauwacke he kens,

The Reid Hill o' Penman, the Bin Hill o' Cullen,

The Dens o' Aberdour, Auchmeddie, and Troup

— Shairly a land nae man can be dull in!

Here's the beach where he catched the Little Stint

Efter lang pursuit, wi' excitement shakin'

Like a cock's tail on a windy day.

Here�s the Balloch Hills wi' forkt lightnin' straikin'

Where he fund the rare mosses and ferns he socht

And here's Tarlair and the muckle rocks

He fell owre to get at a wheen martens aince

— He'd to thole mony fa's and unco sair knocks.

He kent the pretty snappin'–like noise

O' the Death's Heid Moth in its caterpillar state;

Like electric sparks the chrysalis squeaks,

Mair especially aboot its changin' date,

And as for the perfect insect itsel'

He kent a' the range o' its mournfu' tongue

While its muckle bricht een were believed to reflect

The Flames o' Hell frae which it had sprung.

He saw a falcon haudin' a paitrik

In its talons and calmly awaitin' its death,

— Nae expandin' o' a wing to keep balance there,

Nae laceratin' the victim while still it had breath,

Tho' the bird's last struggle gar'd it quiver a wee,

Syne, motionless a meenut mair to be quite

Shair life was extinct, it off wi' the heid

And skinned and carved the rest as a surgeon might.

A heron stared at him wi' its bright yellow e'e

Fu' in the face as if askin' what right

He had in solitudes where the human form

Is sae seldom seen, syne slowly in his sight

Its lang neck doobled quietly doon its breist,

Its dark and lengthened plumes shook, and it rose

Wi' a wild shreik that gliffed ilka bird and beast.

The Sandpiper screamed; the Pigeon cooed;

The Pipit cam' fleein' aboot him; frae the heather

The Moor-cock sprang on its whirring wing,

Curlews and Plovers and a' thegither

Were sairly stirred up, but Tam never moved

Till the inmates o' the glen and mountain aince mair

Disappeared whence they'd come and naething

But solemn stillness resumed its sway there

Tam was a Scotsman o' a splendid type

O' which our puir country is near bereft.

We're a' owre weel–educated noo I doot

To ha'e ony real knowledge — or love o't — left

And as for love o' auld Scotland itself

And knowledge o't, fegs, Tam's pinkie kent

Faur mair than the fower and a hauf millions o's

Livin' the day in oor heids ha'e pent!

He kent the Crenard–star, supposed to ha' been

The maist numerous o' Ocean's inhabitants.

Noo there's only a'e kind in the Scottish seas

And that's rarely seen; and frequented the haunts

O' the Leptochinum — that green Ascidian —

And Drummond's Echiodon, and often longed

To traverse the untrodden caverns o' the deep

For the inconceivable things wi' which they thronged.

He spoke o' each cratur as if ane fell like it

Yet no' the same 'ud be washed up next tide

Or come roon the next corner. His descriptions are final.

He had the seein' eye frae which naething could hide

And nocht that cam' under his een was forgotten.

Fluently and vividly he could aye efter describe

The forms and habits o' a' the immense

Maingie o' animals he saw — an incredible tribe!

A Scot aince as common and noo as rare

As the Crenard–star itsel' in Time's drumlie tide,

First–hand knowledge was what he aye prized

And personal observation was his constant pride,

But oor lives are sae arranged instead

That little o' the life o' the country comes

In to us noo, and even that maun recede

And leave oor haill world nocht but suburbs and slums.

A'e thing is certain —then as noo

Save wi' his ain sel' nae man should fash

Muckle wi' men at a', Man's proper study

Is onything but Man and Tam kent weel

When folk talked o' noxious and dangerous beasts

Nane answered that description in the haill o' nature

Better than maist men — worthless and vicious

To their ain kind and to ilka ither cratur.

***

I had written this and I suddenly thocht

O' ane withdrawn frae the common life o' men

Shut awa' frae the warld in a sick-room for aye,

Yet livin' in what a wonderfu' world even then

— The pure world o' the spirit; less kent

To nearly a'body than Tam's interests even

And I saw in his sangs the variety o' creation

Promise in a new airt mair than a' he was leavin'.

A Scotsman o' a faur rarer type

Than Tam o' the Wilds, and still mair needit,

Tho' still less likely than Tam's kind even

By the feck o' oor folk to be prized or heedit,

— Shair to be scorned, if heard o', for a fool

By the mindless hordes that are fitba' mad,

Or certain that better entertainment than ocht

In nature or spirit in the cinema's had!

God save me frae hasty judgment tho'

When I see infinities in twa sic opposite ways,

For there's nae kennin' what ony man in the mob

May ha'e, in his hert if in nae ither place,

Or deeper than thocht or conscious feelin'

In his sensuous nature and mere animal life

— Laigh or heich in the scale, however we rate it,

There's nae point less than anither wi' God's sel' rife.

O Thou inscrutable, Maker o' a' these,

Wha dealt oot endless hardship to honest Tam

And gar'd him sell his prized collections and brought him

In ruin to the grave, while ithers — no' worth a damn

I micht ha' said; at least they'd naething to show! —

Prospered aboot him; and condemns this ither to lie

Cut off frae life while morons multiply

— In what unreached world yet is your meaning to know?

Membership of FoWSS is free, and you have the opportunity to organise or participate in projects designed to promote Soutar and his works. In addition, members receive an annual newsletter, notification of all FoWSS events and publications, and are invited to an annual Soutar Tea held at the Soutar House. Please use the Contact page if you would like to find out more about FoWSS.